In Your Walls with St Doval, Pete Kyrie & Jay Blues Trio

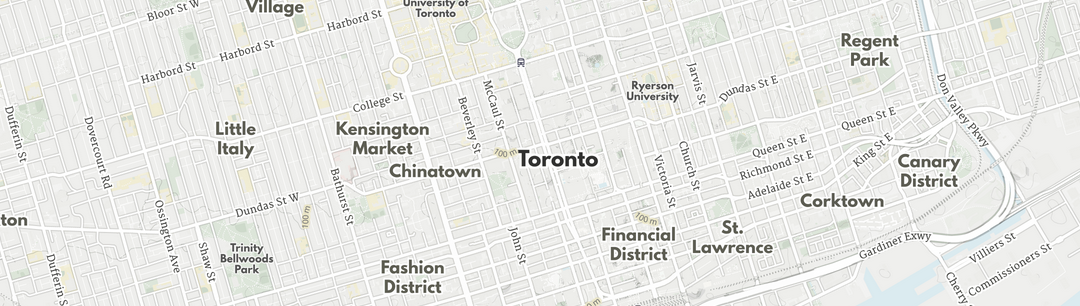

A-Minor Presents In Your Walls with St Doval, Pete Kyrie & Jay Blues Trio. In Your Walls is an alternative rock band from Toronto, bringing a raw, energetic sound to the scene. Formed in 2023, they’re fronted by bassist and vocalist Bridget Puhacz and driven by the powerful rhythms of drummer Syrus Joseph. Their debut EP, S, released in July 2024, combines gritty lyrics and punchy riffs, exploring themes of connection, identity, and city life. Playing gigs around Toronto and London, Ontario, they’re building a reputation for high-energy live shows and are working toward their first full-length album, We are the Walls.