The Best Bread in Toronto

The best bread in Toronto takes the daily staple into dream territory. Be it pillowy and plush, cushioned with butter and eggs, or sturdy with a crackling crust, fragranced with yeast, it's a food that can be topped or toasted, packed with ingredients and squeezed together or simply eaten as is, because it's really that good.

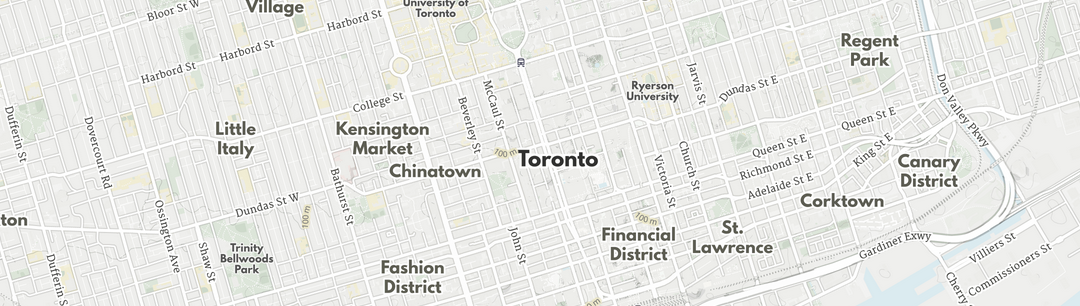

Here is the best bread in Toronto.

Blackbird Baking

Long before it was the thing to do, the team at this bakery (with locations in Riverside, Kensington Market and St. Lawrence Market) was shaping sourdough into life's most essential loaves. Kensington White is a classic, with options from multigrain baguette and brioche to white pullman subbing in when circumstances demand.

Mattachioni Gerrard

In the Junction Triangle and Little India, pizza and pasta stans discover a wealth of doughy delights at this bakery, restaurant and bodega. Fashioned into panini or toted home, fresh-baked sourdough and glistening house focaccia are as much of a draw as the menu's other stars.

Noctua Bread

Pretty things distract from every corner of this Junction bakery, where owner and head chef Daniel Sáez stocks shelves with laminated pastries, pizzas, tarts and breads of every ilk. Crafted from quality ingredients, artisanal loaves — be they rye sourdough; einkorn, oat and maple syrup; baguette or signature pan de nanci — seem to leave the store with nearly every customer.

Bakery Pompette

A third spot for the team behind Pompette and Bar Pompette, this bakery keeps its Little Italy neighbours well-stocked with seriously crusty loaves. What begins with organic Canadian flour and a 24-hour ferment ends with customers cracking into torpedo-shaped baguettes and plump sourdough spheres.

Forno Cultura on Queen

Traditionalist or risk-taker, there's something for everyone at this artisanal Italian bakery with locations in West Queen West, King West, and more. Whether you're team pane Pugliese, focaccia Barese or tomato, guajillo pepper sourdough, you'll find an expertly-made version of it here.

Emmer

On weekends, the lineup at this Harbord Village bakery extends from the front door to the far reaches of the building. Inspired by the team's incredibly fresh and varied bread assortment — which includes sourdough loaves and chubby triple chocolate challah, squishy potato buns and baguettes — people, it seems, will do anything to get their fix.

Johnson Family Bakery

The aroma of yeast draws passersby to this family-run Leslieville bakery, where shelves are stocked with naturally-leavened artisanal loaves boasting bubbly interiors and amber-coloured crusts. Fresh-baked options range from French country miche to spelt sourdough with olives, with seasonal treats popping in and out of the lineup on the regular.

La Boulangerie

The team at this twee Dundas West spot thrills at fashioning enriched doughs and sourdoughs into the types of loaves, buns and twists Toronto can't resist. Popping in for a latte generally means leaving with a sesame seed baguette under one arm, a white Alsatian sourdough under the other, and a pearl sugar brioche dangling precariously from your incisors.

Hector Vasquez

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments