Flower Shop by Wolf & Moon is Toronto's spot for coffee and flowers

Hot Spots

Posted on January 04, 2022

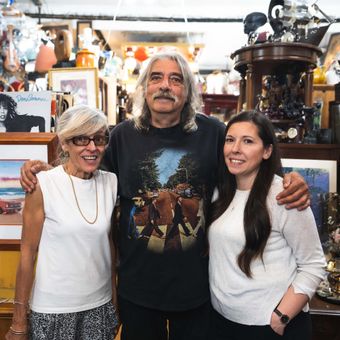

Flower Shop by Wolf & Moon is a Toronto boutique that serves Sam James Coffee and Crown Flora Studio flowers. The concept for Wolf & Moon originated from the owners love of giving gifts.

Produced by Aaron Navarro. Filmed and edited by Briana-Lynn Brieiro. Hosted by Tiana Atapattu

Your inspiration for places to eat and things to do in Toronto. Plus news, events and more. New videos posted daily. View all videos