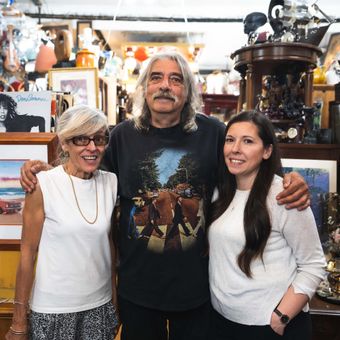

Wayland Li Martial Arts Centre in Markham is a competitive school led by a wushu master

Hot Spots

Posted on September 29, 2021

Wayland Li Martial Arts Centre is a school outside Toronto teaching the fundamentals of wushu, also known as kung fu. This Chinese martial art is most commonly found in iconic kung fu movies, including Marvel's Shang Chi.

Produced, filmed and edited by Aaron Navarro. Hosted by Taylor Patterson.

Your inspiration for places to eat and things to do in Toronto. Plus news, events and more. New videos posted daily. View all videos