Silencia Eyewear is Toronto's source for custom-made glasses

Hot Spots

Posted on November 25, 2020

Silencia Eyewear is an online store from Toronto that makes laser-cut glasses inspired by the city's queer community and culture.

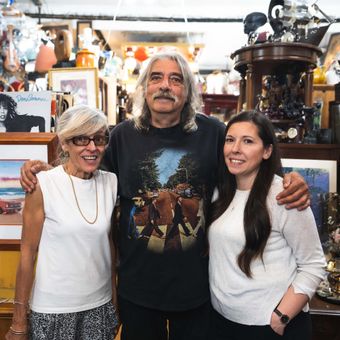

Produced by Aaron Navarro. Filmed and edited by Jason Pham. Hosted by Mercedes Gaztambide.

Your inspiration for places to eat and things to do in Toronto. Plus news, events and more. New videos posted daily. View all videos